What recent research tells us

Nursing homes are a big deal. Over a million people each year pass through one of America’s 15,600 nursing homes each year, with the government spending $83 billion a year out of a total cost of $160 billion. That’s about 5% of total health expenditures in the United States.

In recent years, there has been an incredible bounty of high quality research on nursing homes, all made possible by the exceptional data which has been collected. Unlike most medical care, where data, especially in a standardized form, is often hard to come by, the CMS requires regular assessments of all nursing homes, with detailed data on patients and staffing measures. (We could do so much to improve health – evaluate public policy, train AI models – if we had less strict medical privacy laws). Researchers are also able to use extensive payroll records on who works in nursing homes. We have used this for a few main lines of research.

First, how much do nursing homes differ from each other in quality? And how can we predict from observables which nursing homes will be better? This is important for two reasons. If some nursing homes are systematically better than others, then we could improve health outcomes simply by reallocating from home to home. Even better, if we could observe what was correlated with better health outcomes we might have a guide to policy to improve nursing homes. Second, how can we improve nursing homes? What are some policies which regulators could implement to provide better care at less cost? And what can nursing homes themselves do to improve their quality?

When it comes to measuring nursing home quality, Einav, Finkelstein, and Mahoney (2025) is the key paper here. Unfortunately, their results are a mixed bag. While they find considerable heterogeneity of outcomes across nursing homes which remain after controlling for the region, they do not find reliable predictors of outcomes outside of patient composition.

Finding the effect of nursing homes is not a trivial task, with two main challenges. First, patients might sort themselves between nursing homes, and nursing homes might exert some selection over their patients, in a way that cannot be gotten rid of simply by controlling for everything we can observe. Second, nursing homes influence when the patients leave the nursing home, in particular causing them to leave the nursing home before the 30-day assessment. We cannot observe what happens to health after that point.

For the first problem, they use the distance from a nursing home as an instrumental variable. The assumption is that distance changes which home you select, but is uncorrelated with other determinants of health except through choice of nursing home. To support this, they show that adding additional controls for patient type does not upset this association. For the second, they estimate a threshold of health beyond which each specific nursing home tends to discharge patients.

As of yet, there is no publicly facing application which uses Einav, Finkelstein, and Mahoney’s data to let you yourself decide which nursing home to use. I think that this would be an extremely useful exercise, and one which they should pursue.

So what can we do to improve patient outcomes and efficiency? One thing to do is change how we do inspections. Every nursing home is required to be inspected about once a year by a trained professional, who notes down failures of the nursing home in over 200 possible categories. These sorts of oversight programs are effective at reducing mortality, just as audits are effective at reducing wasteful spending (see “ Monitoring for Waste ” by Maggie Shi for more on the effect of audits in the world of Medicare – every dollar spent on auditing reduces spending by 24 dollars, with no change in patient outcomes).

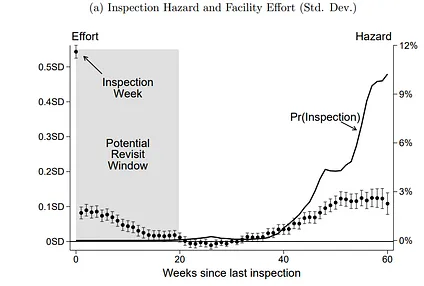

As noted, inspections occur about once a year. This means that the inspections aren’t really randomized – they come on a regular, predictable cycle. As you can see in the graph below, the measure of effort – a composite of staffing levels and choice of staff – changes over the year, as nursing homes prepare for a coming inspection.

Ashvin Gandhi, Andrew Olenski, and Maggie Shi (2025) estimate how much we could decrease mortality if inspections were actually randomized. They estimate that it would increase effort by as much as having 12% more inspections would. Translating that into an effect size on real variables, the current threat of inspections saves 850 lives a year and the new policy would save 954.

Gandhi, Olenski, and Shi cite Ball and Knoepfler (2023) as background literature for the optimal timing of inspections. I like the paper, and it’s my blog, so we’re detouring to cover it.

Suppose you want to make sure that the work you want done is being done. You have the ability to inspect at any time by paying a fixed cost. The standard result is what you should always randomize, but that is not what Ball and Knoepfler find. They find that you should inspect on regular schedules if the project will mostly lead to “breakthroughs”, which terminate the project, and you should inspect randomly if it mostly leads to breakdown. The difference in results boils down to what exactly the inspection technology is. In the standard results, the inspection can detect if the agent is shirking at that moment, but not a moment before. Here, they leave behind some evidence of what they were doing in the period before.

Both principal and agent discount the future, and so want to push off future inspections. Suppose breakthroughs are more common than breakdowns. If an agent plans to shirk, then they expect the project to end later, and thus they are relatively more patient. They know that if they want to keep the project going, they should start working in preparation for the scheduled inspection. By contrast, with breakdowns prevail, they will be relatively more impatient. Inspections should come randomly, at just a high enough rate to induce working at all times.

There is a sort of anti-climax to the question of nursing homes. The inspection technology is obviously something which can detect past infractions – even a mad scramble of cleaning is unlikely to get everything ready in time. However, it’s also obviously something where breakdowns predominate.

What about things which nursing homes could do? Cheng and Hackmann (2025) consider the influence of your roommate on health outcomes. Nursing homes come either with single or double rooms, and patients are generally not transferred between rooms once they enter. Thus, we can use which beds were available at the time of admission across millions of patients as a source of exogenous variation in roommate type and number.

They find that there is an important heterogeneity across cognitive health status. Cognitively healthy patients do better with single rooms, while patients with Alzheimer’s do better with a cognitively healthy roommate. Cognitively healthy patients are made equally worse by whatever kind of roommate they get, so we could improve things by simply assigning healthy patients to single rooms, and pairing healthy and unhealthy patients together.

The benefits are staggeringly large for a change which is free – a reduction in overall mortality by.8 percentage points, or 50 lives saved a year. Remarkably, these mortality benefits do not come with the perhaps unwanted effect of increasing government expenditures. People really do get better and leave the nursing home. This leads to the government actually saving money.

Many of these firms are for-profit, although they are heavily reliant on government spending. They claim to be losing money, and the sector as a hold appears to be relatively unprofitable. This is not true. In order to gain a better negotiating position, firms misrepresent their profits in ways that border on – or are simply – fraud. Medicare has difficulty telling how much something should “really” cost, and defaults to compensating the observed costs, plus some profits.

The most common subterfuge is to sell the physical assets of the nursing home to a company which is owned by the same people, then lease it back at outrageous rates, followed by hiring management company (yourself) which you pay an inflated fee too. Gandhi and Olenski (we’ve heard those names before) show that the actual profit rates of nursing homes are two and half times higher than they claim. They have data from the state of Illinois, which requires considerably more reporting of nursing home transactions than other states. Renting from a related party increases the cost of real estate by 42%; the property was itself sold for 20% less than its real value; and paying a management company which you owned increased the cost of management by 25%. The CMS needs to collect this data, and see through it when negotiating over the standards of care to be used.

While profit rates are understated, we should remember that we get the healthcare which we pay for. Hackmann (2019) studies what happens when Medicaid reimbursements increase. The number of skilled nurses increases considerably – by 8.7%, for every 10% increase in reimbursement rates.

One reason they want to appear to be struggling is so that they can get permission to merge with other nursing homes, or be bought out by other providers. This has been especially controversial lately, with many people on the progressive side of the political spectrum charging private equity with providing less and worse care. The evidence for this is mixed, but it does seem that private equity reduces the quality of care provided, depending on the strength of competition.

We face many of the same issues as before. Private equity could select patients more aggressively, leading us to misstate the effect on patients. Gupta, Howell, Yannelis, and Gupta (2024) use distance, as Einav, Finkelstein, and Mahoney did, as an instrumental variable for selection. Note that the patient effects are not through a difference-in-differences approach, but rather through a takeover changing the local nursing homes available. Private equity firms tend to take healthier patients, but after adjusting for this, mortality increases. This seems to be coming largely through a reduction in staffing levels.

Gandhi, Song, and Upadrashta (2025) have an interesting story to tell, where the effects of private equity are entirely dependent on local competition. If the local market is uncompetitive, then private equity firms are essentially specializing in exploiting the market power which the previous owners were unwilling or unable to exploit. If it is competitive, then the better management practices they bring end up benefitting the consumers. Chatterji, Ho, and Li (2025) study mergers in general, and find that absorbing independent facilities into chains increases the quality of nursing homes, consistent with knowledge and managerial practices being spread.

I am not convinced by the case for totally banning private equity investment into nursing homes. To the extent that there are problems, it seems to be due to them picking up the slack which regulators have left to nursing homes. Better to regulate quality, which is what actually matters, than to very indirectly regulate who buys who. There is nothing special about “private equity” – it’s just a way of raising capital. To actually prevent the bad outcomes caused through this channel, you would need to simply ban buying and selling nursing homes – and that would be treating a rash with a hammer.